Over 7% of U.S. adults have experienced major depression in the past 12 months (nearly 18 million adults). About two-thirds of adults with depression have what’s categorized as “severe” depression. Severe depression often is accompanied by comorbid conditions, meaning that both physical and mental health conditions frequently co-occur. For people with severe depression and comorbidities, it can be really hard to function during daily life. They might use the healthcare system more than most, miss work more often, feel less productive, and have an overall decreased quality of life. Depression currently ranks second among all diseases and injuries in the U.S. as a cause of disability. Severe depression, in particular, can be life threatening due to increased risk of suicide.

People with severe depression often end up trying several different interventions, most often medication and psychotherapy. Alternatives include TMS, ECT, vagus nerve stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and ketamine treatments. In terms of treatment that’s available now, it’s difficult to find an intervention that is quick-acting, long-lasting, and free from harmful side effects.

Accessible and effective treatments are critical to treating severe depression. Several digital health interventions have shown promise in treating depression, particularly those that include clinician support — this is exciting, because digital treatments reduce barriers to care and are free from side effects. But, few digital interventions have been tested for people with more severe forms of depression. That’s why the research team at Meru Health wanted to focus on how digital forms of treatment impact this population in particular.

What was the intervention?

A group of 218 patients with moderately severe to severe depressive symptoms participated in the 12-week Meru Health mobile program, delivered via smartphone app.

In order to qualify for the study, patients needed to have at least mild levels of depression, anxiety, or burnout, own a smartphone, and not have an active substance use disorder, severe active suicidal ideation with a specific plan, severe active self-harm, or a history of psychosis or mania.

Study participants participated in Meru Health’s 12-week self-guided intervention, delivered on a mobile app.

The intervention includes components of several evidence-based practices, including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Behavioral Activation Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, as well as some promising new treatments for depression and anxiety including sleep therapy, nutritional psychiatry, and heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB).

At the beginning of treatment, patients completed an intake call with a therapist and were trained on how to use the app. At the beginning of each week, patients would complete an intro video with an overview of topics for the week, which would unlock the week’s content. Participants were prompted to engage with the app on a daily basis (for about 5 to 15 minutes).

Study participants had access to chat-based daily interaction with a licensed clinical therapist, and there was a medical doctor and psychiatrist available for consultation as needed, and in case of emergency. Patients are part of a cohort of around 8 to 15 other participants — within this group, they can interact anonymously and share about their practice experiences.

How were outcomes measured?

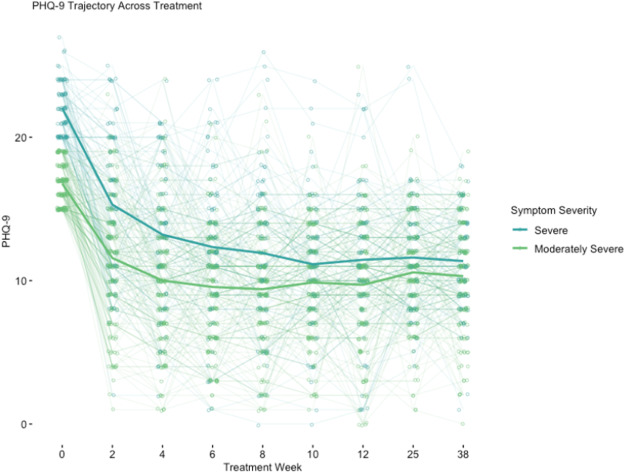

This study used the PHQ-9 to assess severity of participant depression at baseline, during treatment, and after treatment. The PHQ-9 is a 9-question test used to diagnose the severity of depression.

PHQ-9 scores range from:

- 0–4: No depression / minimal depression

- 5–9: Mild depression

- 10–14: Moderate depression

- 15–19: Moderately severe depression

- 20–27: Severe depression

The average baseline score for patients taking part in the study was 18.60 (moderately severe depression).

PHQ-9 scores were assessed before the start of treatment, every 2 weeks during the 12-week treatment period, and at 3 and 6 months after the intervention was complete. The changes in PHQ-9 scores during treatment and the follow-up period up to 6 months post-treatment were adjusted for things like baseline values of depression, demographic characteristics, and engagement with the program (number of days participating in the program and minutes of HRVB practices).

What were the findings?

Takeaway: This study of people with severe depressive symptoms found that by using Meru Health’s mobile intervention, people had significant decreases in depression that were maintained over time.

At end-of-treatment, for patients who had moderately severe depressive symptoms, their PHQ-9 scores dropped by an average of 7.06 points (a 41.80% reduction). For patients who came in with severe depressive symptoms, their PHQ-9 scores dropped an average of 10.6 PHQ-9 points (a 47.30% reduction).

Also, 34% of patients with at least moderately severe depressive symptoms at baseline and 29.9% of patients with severe depressive symptoms at baseline had a 50% reduction in symptoms plus a final PHQ-9 score lower than 10 (a score lower than 10 indicates that someone is no longer clinically depressed).

A majority of study participants (71.6% in the moderately severe group and 90.9% in the severe group) experienced a clinically significant decline of 5 or more PHQ-9 points between baseline and end-of-treatment assessments.

Importantly, these drops in symptom severity were sustained 6-months post-treatment.

Dr. Valerie Forman-Hoffman, lead researcher for this study and Chief Research Officer at Meru Health says, “We intend to share our findings with customers who might be hesitant to offer our treatment program to their members with more severe depressive symptoms to boost confidence in the efficacy of our product for these individuals. Severe depression can be life-threatening, so the more efficacious solutions we have on the market, the more likely we can save these individuals from suffering from its effects.”

What does this mean for the future?

The future of mental health care is accessible and effective.

The Meru Health mobile intervention studied addresses many of the barriers that typically keep patients from starting and continuing care:

- Pharmacological treatments have side effects and can take 4 to 6 weeks to

take effect. - ECT, brain stimulation, and Ketamine often have fast-acting results, but

aren’t sustained over time. - In person appointments are often inaccessible for people’s schedules, in

rural or remote areas, due to scarcity of clinicians, due to lack of transportation, and due to the stigma that

surrounds seeking in-person mental health care.

Mobile interventions like Meru Health can be done in a way that’s self-paced, convenient, and private — in addition to being more accessible, people experience a significant improvement in their depression symptoms that actually last over time.

This groundbreaking research will contribute to the broader field of digital mental health. According to Dr. Valerie Forman-Hoffman, “While this is not the first efficacy study of a digital mental health solution for those with more severe depressive symptoms, we are one of the first to show the sustainability of the improvements of symptoms up to 6 months post-treatment. Because our solution also helps patients overcome several treatment barriers, patients might be more willing and able to enroll in the Meru Health treatment solution than other treatment types.” Dr. Forman-Hoffman leaves us with a message of hope: “The more patients we can reach, the more we can help them recover.”

Reference:

Forman-Hoffman, V. L., Nelson, B. W., Ranta, K., Nazander, A., Hilgert, O., & de Quevedo, J. (2021). Significant reduction in depressive symptoms among patients with moderately-severe to severe depressive symptoms after participation in a therapist-supported, evidence-based mobile health program delivered via a smartphone app. Internet Interventions, 25, 100408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100408